This blog post is the first in a series where members of the ADEP Organizing Team will explore what it means to organize collectively as Afghans. Through these blog posts, we hope to spark a conversation as to what it means to not just fight for each other, but with and for others. We are not simply victims of imperialism who are subject to the longest war in US history — to make such a claim would erase our power, as well as our complicity in harm. In this first post, we will be exploring what it means to support Black Lives and Black Liberation as Afghans.

We are in the midst of one of the longest ongoing uprisings in this country, but the fight for Black Liberation is nothing new. To actively engage in and support Black Liberation, we must examine our community critically and see where we have fallen short, where we can improve, and what we have done right. To examine ourselves in this way, we will draw from the work of The Combahee River Collective, specifically their work on identity politics.

In the mid-1970s, a group of Black Feminist scholars and activists started meeting to address the very specific concerns of Black women, since the feminist majority at the time ignored Black women. They outlined their concerns in their 1977 work, “A Black Feminist Statement.” Specifically, The Combahee River Collective formulated the concept of identity politics. In their statement, they outline that the only ones standing up against their oppression are themselves and, therefore, they are “actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression.” Identity politics is not, as it is often misinterpreted to be, simply holding an identity. Instead, it is how we engage politically to preserve that identity. That is, how can we engage in politics in a critical way. In a way that takes into account our position within our host countries as opposed to engaging in shallow ways that urge Afghans to strive for only representation or assimilation into the very systems that oppress Afghans living in Afghanistan. For Afghans, what does it mean to preserve our identity, particularly for those of us living in the United States?

Let’s look at two examples of how identity politics is used in the Afghan diaspora, one which simply asserts our identity as Afghan and another which actually strives to preserve it.

There is a more common way identity politics can be misunderstood in the United States, in particular. This misunderstanding is based on ideas of assimilation and power–that is, we must prove to someone else that we can be successful or that our presence as an Afghan alone is indicative of change being made. This is not a problem unique to our community, but it manifests in very particular and insidious ways, such as participation in institutions causing harm to Afghans and other marginalized people. Although we understand the complex reality that has driven our fellow Afghans to work for, say, the US military, the police, or even the Department of Homeland Security, we still condemn it wholeheartedly. This is the same line of thinking that leads to diaspora Afghans returning and assuming positions of power within Afghanistan.

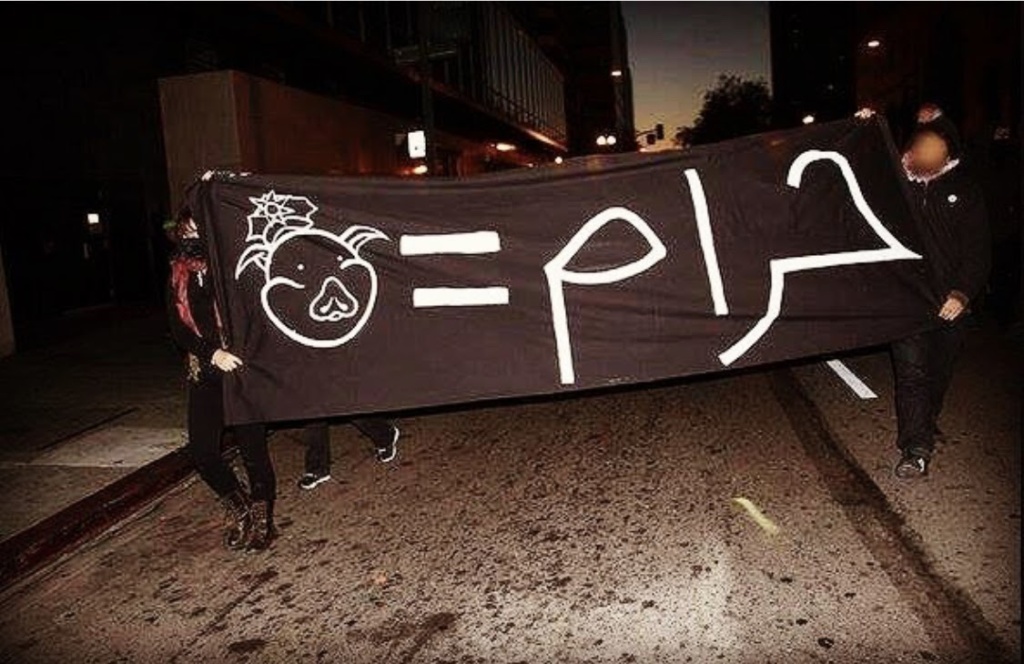

Instead of doing work which causes harm and which requires us to make our identity palatable to the white gaze, we should instead focus on our identity in a way more in line with what the Combahee River Collective outlined. In 2009, Oscar Grant was murdered at a BART station in Oakland by the police. This rightfully sparked an uprising that cost the city $200,000 in damages. Afghans were a part of this uprising; they carried signs that said “All Pigs Are Haram” (a slogan becoming more and more popular with abolitionist Muslims). For their support of the uprising, the Afghan leaders were harassed and surveilled by federal officials. Despite this, they mobilized a rainbow coalition of supporters once again to shut down a military recruitment center in Oakland following the Kunduz hospital bombing. Those same people are still active in the ongoing uprisings and are still being surveilled and harassed. But we are beginning to understand our collective power as Afghans.

To understand our power, it is important to recognize the ways our identities have informed who we are as activists. For example, there are material connections between police violence, militarization, and imperialism that affects Afghanistan and other subjects of occupation around the globe. These connections are a product of ideological connections between the US and other imperialist forces. Though there are many examples of this connection, we focus on two — (1) the training of US police with members of the Israeli Defense Force, and (2) US federal programs allowing for the transfer of military equipment to police forces.

First, US police train with the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), a military that enforces the occupation, apartheid, and the settler-colonial state in Palestine. Law enforcement from Florida, Maryland, Pennsylvania, California, New York, and many other states have all travelled to Palestine to train with Israeli officials. Thousands of other law enforcement have received training from Israeli forces here in the US. The IDF is distinctly linked to extrajudicial executions, unlawful killings, torture, surveillance, and excessive use of force. IDF violence in Palestine employs a similar logic to police violence in Black communities in the U.S. The victims of violence are predetermined by a racialized logic that purposefully undervalues particular lives — Black individuals are targeted by police in the U.S. to uphold “white” ideals and society, and Palestinians are targeted by the IDF to fully establish an Israeli state while ethnically cleansing the Palestinian people, identity, culture, and land.

This predetermination forces us to reframe how we think about how a “violation” of the law is not what leads to violence, but rather death and violence are already prescribed to a population at the outset. In Palestine, Ahmed Erakat was killed by the IDF for getting out of his car to check his tires near a checkpoint. In the U.S., Breonna Taylor was sleeping in her own bed, in her own home. In Afghanistan, civilian life is targeted regularly and systemically by employing attacks on people’s homes, places of worship, markets, and schools. Death and violence have already been prescribed to these populations because state violence against Black people in the US is indiscriminate in much the same way that civilian casualties in Afghanistan are indiscriminate: both are framed as justifiable collateral. The point is that the imperialist state benefits from devaluing these lives for the purpose of Black labor in the US, devaluing Palestinian lives for the purpose of eliminating a so-called “demographic threat,” and devaluing life in Afghanistan for the purpose of extracting resources and benefiting military contractors for prolonging the war in Afghanistan.

Second, US federal programs also allow for the transfer of military equipment to police departments, including direct purchases of equipment. The 1033 Program allows for the free transfer of excess military equipment from the Department of Defense to law enforcement agencies at federal, state, and local levels. According to the Law Enforcement Support Office, which oversees this transfer process, “over $7.4 billion of [military] property has been transferred since the program’s inception; more than 8,000 law enforcement agencies have enrolled.” Poor record keeping has meant that some of this equipment is also unaccounted for and there is no publicly available information of where this equipment has been transferred. The training to use this equipment is also not standardized, necessarily leading to misuses that can cause dramatic and incredibly harmful practices. The 1122 Program also allows for state and local governmental units to purchase law enforcement equipment from the Department of Defense that are suitable for counter-drug activities. These militarized weapons and tools are more often deployed in communities of color, and contrary to claims by police administrators, provide no detectable benefits in terms of officer safety or violent crime reduction.

These examples demonstrate how interconnected and interdependent the lives of those affected by imperialism and colonialism are. It is thus even more critical to make our solidarity as Afghans concrete. Solidarity requires sacrifice though — it requires our labor, our money, and a reckoning with our own complicities in a racist system. This means that it is critical to show up to protests and actions. Liberation movements are quashed when individuals become indifferent and stop showing up for issues that matter. It is also critical to donate to mutual aid funds or provide mutual aid in communities. In this particular moment in history, we understand that a global health pandemic can limit how or when we show up to a protest or action. Showing up by donating to liberation causes is just as important.

Our labor for the Black Lives Matter movement does not require our community to reinvent the wheel. Rather, to be a part of this movement is to recognize that there are many who have done this work for years and know more about the complexities of liberation movements than we do. Part of our role is then to learn from others, unlearn our own biases, and work as collaborators to already established organizations, including organizations like Critical Resistance, INCITE!, Moms for Housing, and Black and Pink.

The role that we play also includes recognizing our complicities – being a part of the state apparatus that enforces our current racist system is a part of the problem. This means that being in the army, being a police officer, being a prosecutor, or working for the State Department is a part of the problem. Those in our community who are in this system must stop participating in it. It is, thus, also critical to prevent recruiters from the US Army, police, or any other law enforcement-type agency from recruiting out of our high schools and colleges to prevent the ongoing exploitation of young people of color in these racist systems.

For more information, ADEP has put together a toolkit on how Afghans can support the Black Lives Matter movement.

Add Comment